§08. Belief and the Sense of Truth (Konstantin Stanislavski, An Actor’s Work)

THEATRE

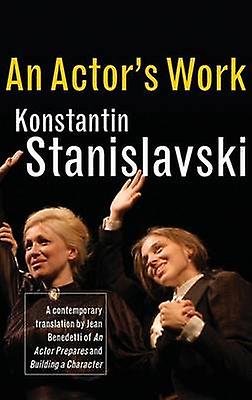

This article is my summary of the eighth chapter of An Actor’s Work by Konstantin Stanislavski. This book is a new edition and English translation by Jean Benedetti of the material previously published under the titles « An Actor Prepares » and « Building A Character« .

Previous chapter: §7. Bits and Tasks (Konstantin Stanislavski, An Actor’s Work)

Next chapter: §9. Emotion Memory(Konstantin Stanislavski, An Actor’s Work)

Table of contents: An Actor’s Work (Konstantin Stanislavski)

What are Truth and Belief onstage ?

Truth onstage does not have the same meaning as in real life.

“In life there is truth, what is, what exists. (..) Onstage we call truth that which does not exist in reality but which could happen.” (p. 153)

Therefore, Truth onstage is closely related to Belief.

“Truth onstage is what we sincerely believe in our own and in our partners’ hearts.” (p. 154)

“Truth is inseparable from belief, and belief from truth. They cannot exist without each other (…).” (p. 154)

Stanislavski mentions three features of Truth on stage:

- It’s not of a Truth of the material world, but of the Feelings

- It’s not a truth-like, but a genuine Truth

- It’s not a naturalistic Truth, but an artistic Truth

Truth of the material world or Truth of the Feelings ?

The object of Truth and Belief onstage is not the material world (which often isn’t true), but the Actions and the Feelings related to them

“What is important is not whether Othello’s dagger is papier mâché or metal (…). The important thing is that the actor/human being should behave as though the circumstances and conditions of Othello’s life were genuine and the dagger with which he stabs himself was real.” (p. 154)

“Decide (…) what it is you want to believe, that the material world of facts and events exists in the theatre and in the play, or that it is the feeling which is born in the actor’s heart, stirred by a fiction, that is genuine and true. That is the truth of feeling we talk about in the theatre.” (p. 154)

So the actor should ignore the things which are not the object of the Truth and Belief we are looking for (for example the falseness of props).

“The actor must become involved with the things he can believe in and take no account of things which are a hindrance to him. That will help him forget the black hole and the condition of appearing in public.” (p. 156)

Truth-like or genuine Truth ?

The Truth needed in the Art of Experiencing should be a real and genuine one, and not a truth-like, as in the Art of Representation.

“Your [in the art of representation] sham truth helps you represent ‘characters and passions’. My truth [in the art of experiencing] helps us create the characters and the passions themselves. Between your and mine there is the same gulf fixed as between the words ‘seem’ and ‘be’. I need genuine truth, you are satisfied with the truth-like. I need belief, you limit yourself to the belief the audience has in in you. (…) In your kind of acting an audience is an audience, in my kind it becomes an involuntary witness of and a participant in the creative process.” (p. 187)

Naturalistic or artistic Truth ?

To be genuine, theatrical Truth must be Realistic. But that does not mean it has to be naturalistic to the point that the actor should bring onto the stage every aspect from the real life. There are things from real life that would be harmful for the artistic Truth and would lead the actor to Playacting.

“[There are] many theatre managers, actors, audiences, critics who love and acknowledge only the slice of life, naturalism, realism onstage – the truth.” (…) There is an element of exaggeration, (…) when simplicity and naturalness verge on ultra-naturalism. [This extreme borders] on the worst kind of playacting.” (p. 157)

“Why, when we don’t need it, should we take things from life which we should reject as unnecessary dross ? Tasks and truth of this kind are anti-artistic and so is the impression they leave behind. The repulsive doesn’t create the beautiful (…) So, not all the truths we know in life are good for the theatre.” (p. 192)

“There is the same difference between artistic and unartistic truth as there is between a portrait and a photograph. The latter gives you everything, the former only the essential. (…) [There] are photographic details which are harmful to a picture.” (p. 192)

Stanislavski explains the difference with the example the staging of a man’s death.

“We want a single, essential feature or other, which characterizes a man dying, and not by any means all the symptoms he gave us. Otherwise the important thing, the death, the departure of someone dear, is pushed into the background, and secondary symptoms stand out, and the audience will feel sickened at the very moment when they should be weeping.” (p. 192)

Therefore, Truth on stage must be selective: it should retain the essential things from the real life, while deciding to leave unnecessary ones behind. This way Truth on stage will be not only Realistic, but artistic and poetic as well.

“Truth in the theatre must be genuine, not glamorized. It must be purged of unnecessary, mundane details, it must be true in a realistic sense but made poetic by creative ideas. Let truth onstage be realistic, but let it be artistic.” (p. 192)

“By taking what is most essential into ourselves, endowing it with the beauty of form and expression appropriate to the stage, by paring away what is superfluous, with the help of our subconscious (…) we turn the role into something poetic, beautiful, harmonious, simple, comprehensible, ennobling and purifying for the audience. These qualities help what we create onstage not only to be truthful and truth-bearing but artistic as well.” (p. 193)

“Whatever is subtle, truthful, is invariably of high artistic quality.” (p. 194)

Why are Truth and Belief onstage important ?

Stanislavski sees Truth and Belief as essential features of theatre.

“There is no genuine art without truth and belief.” (p. 154)

He acknowledges that there are some people who would disagree, people who don’t want to see Truth on stage. But such view can only result in Playacting.

“There are many theatre managers, actors, audiences, critics who only love conventions, the theatrical and wrong onstage. (…) The real world bores them, and they don’t want to have to face it onstage. (…) to avoid it, they look for as much distortion as possible (…) There is an element of exaggeration, when (…) contortion [is] taken to such extremes it verges on deformity. (…) [This extreme borders] on the worst kind of playacting. ” (p. 156)

For Stanislavksi, Truth and Belief are important both for the actor and the audience.

Why are Truth and Belief important for the actor ?

The actor should create and feel Truth and Belief every moment he is onstage.

“Everything onstage must be convincing for the actor himself, for his fellow actors and for the audience. Everything should inspire belief in the possible existence in real life of feelings analogous to the actor’s own. Every moment onstage must be endorsed by belief in the truth of the feelings being experienced and in the truth of the action taking place. “ (p. 154)

“Everything the actor does (…), connected with the inner and the outer line of actions, needs to be monitored and sanctioned by the feeling of truth.” (p. 194)

Truth and Belief are indeed necessary conditions for the process of Experiencing to take place. They will give the actor the impulse to perform his Actions genuinely and allow him to access to Feelings.

“Without [truth and belief] there can be no experiencing of creative work.” (p. 154)

“Where truth, belief and ‘I am being’ are, inevitably you have genuine, human (and not theatrical) experiencing. These are the strongest ‘lures’ for our feeling.” (p. 186)

“Having felt inner and outer truth and believing in it, an impulse to action automatically arises, and then action itself.” (p. 169)

“[The actor] felt the truth, the life of his actions and began to perform them genuinely, productively and purposefully.” (p. 170)

Why are Truth and Belief important for the audience ?

What the audience wants is to be captivated by what is happening onstage. For that, they need to be able to Believe in what they see.

“The audience in a theatre wants to be ‘taken in’, it likes believing in theatrical truth and forgetting that’s all play and not real life. Win over the audience with the genuine truth and belief in what you are doing.” (p. 177)

“What a good audience wants most of all is to believe everything, it wants to be convinced by a story.” (p. 176)

“You don’t shed tears over something you don’t believe in.” (p. 188)

Why do Truth and Belief onstage need to be consciously created ?

Onstage there is no reality, which can act as a given Truth and automatically inspire Belief, as in the real world. There is only a fictional world, created by the actor’s Imagination. Therefore, the Truth of this world, and the Belief in it, must also be created by the actor.

“In the real world, genuine truth and belief create themselves. (…) But when there is no reality onstage and you have acting, then the creation of truth and belief needs to be prepared in advance. That means that truth and belief first arise in the imagination, as an artistic fiction, which is then translated onto the stage.” (p. 153)

Sometimes Truth and Belief in the stage fiction will appear on their own, and that’s for the best. But when it’s not the case the actor needs a technique to make them appear.

“The best thing for an actor is when truth and belief in the reality of what he is doing arise spontaneously. But what about when that doesn’t happen ? Then you have to search for and create this truth and belief yourselves using your psychotechnique.” (p. 160)

How to create Truth and Belief onstage ?

What should the actor focus on ?

Even though the Truth the actor is looking for is a Truth of the Feelings, he shouldn’t create it in his Feelings, through inner actions, but in his body, through Physical Actions.

How are you to create truth and belief within yourselves ? (…) The easiest thing of all is to find and stimulate truth and belief in the body, with the tiniest, simplest physical Tasks and actions.” (p. 160)

Why should the actor focus on the Truth of Physical Actions and not of the Feelings ?

Feelings are elusive and complex. If the actor would focus on the Truth of them, he would be tempted to force them and would run the risk of Playacting. Focusing on the Truth of Physical Actions protects the actor form this risk, by giving him something concrete and easy to hold on to.

« [Inner feelings and actions] are too complex, elusive (…) [Physical Tasks and actions] are accessible (…), they submit to the conscious mind and to orders.” (p. 160)

“Tell an actor that (…) his actions are psychological, profound, tragic and he will immediately tense up and playact passion (…). But if you give the actor the simplest, physical Task within interesting, exciting Given Circumstances, then he will start performing it (…) without thinking whether there is psychology, tragedy and drama in what he is doing. (…) Feeling is not forced and develops naturally and fully” (p. 165 s.)

“The nearer action is to being physical the less risk you take of forcing your feelings.” (p. 180)

“Forget about the audience and the effect you’re having on them and instead of trying to charm them, confine yourself to small, physical, realistic actions, small physical truths and a sincere belief in their genuineness.” (p. 164)

“We like physical actions, too, because they help us fix our concentration on the stage, the play, the role and focus on the line of the role we have firmly established.” (p. 166)

“If you can’t master everything all in one go just give me part of it, just establish the line of the outer physical actions. Feel the truth in it.” (p. 177)

This is especially the case for moments of intense tragedy.

“Small physical actions, small physical truths and moments of belief assume great importance not only in simple passages, but also in very intense, climatic moments when you are experiencing tragedy and drama.” (p. 164).

“In moments of intense tragedy, the actor has to reach the highest point of creative tension. That is difficult. Indeed, an enormous effort is needed to reach a state of abandon when you have no natural urges to drive you on ! (…) It is all too easy to jump the track and come up with mere stock-in-trade, histrionics and playacting, when you have muscular tension in place of genuine feeling. (…) It’s the line of least resistance.” (p. 165)

“To avoid making this mistake, you need to take hold of something real, stable, organic, tangible. For that we need some clear, clean, exciting but easily doable physical action that typifies the moment we are experiencing. This sets us on the right path naturally, automatically and doesn’t let us veer off on wrong paths at moments when creation is difficult.” (p. 165)

But focusing on true Physical Actions doesn’t mean giving up on Feelings. Quite the opposite: Physical Actions will lead the actor to the Feelings of the role, but in an easy and imperceptible way.

“We like physical actions because they lead us easily and imperceptibly to the very life of the role, to the feelings it contains.” (p. 166)

“As soon as I felt the truth of physical action I felt at home on the stage. And at the same time, spontaneously, impromptu actions occurred.” (p. 161)

“I need technique and physical actions so that, with the help of truth and belief, I can convey complex human experiences.” (p 190)

Therefore, if Physical Actions are important, it’s not as such, for the sake of Naturalism, but because they are the easiest way to the Truth of Feelings.

“The secret of my method is clear. It’s not a matter of the physical actions as such, but the truth and belief these actions help us to arouse and feel” (p. 162 s.)

“In time you will understand that this has to be done not for the sake of naturalism but for truth of feeling, so as to believe it is genuine.” (p. 165)

“Don’t neglect small physical actions but learn to use them for the sake of truth and your belief in the genuineness of what you are doing.” (p. 164)

How can Truth of Physical Actions lead to Truth of Feelings?

There is a strong interaction between Feelings and Physical Actions.

“In life itself experiences of a high order are very often revealed in the most ordinary, little, naturalistic actions.” (p. 165)

But this interaction happens only when Actions are performed within the context of the Given Circumstances.

“[The] physical actions acquire great force within the context of the Given Circumstances. Then there is an interaction between mind and body, action and feeling, thanks to which the outer helps the inner, while the inner stimulates the outer.” (p. 165)

Why are the Given Circumstances of the Action important for Truth of Feelings ?

It is the Given Circumstances which give a Physical Action its particular meaning and force.

“Often the difference between drama, tragedy, farce and comedy only consists in the Given Circumstances in which the actions occur. In all other respects physical life remains the same.” (p. 166)

“The important thing is why it is done. The important things are the Given Circumstances, the ‘if’. They bring an action alive, justify it. An action acquires a quite different meaning when it occurs in tragic or other circumstances in the play.” (p. 166)

Therefore, it’s only if the actor’s Physical Actions are properly justified through Given Circumstances that they will help him create Truth and Belief. The actor should conduct this process of justification for each Action he does onstage.

“The magic ‘if’ and Given Circumstances, when they are properly understood, help you to feel and to create theatrical truth and belief onstage.” (p. 153)

“Always try and justify what you do onstage with your own ‘if’ and Given Circumstances. Only by creative work of this kind can you satisfy your sense of truth and your belief in the genuineness of your experiencing. This process we call the process of justification.” (p. 154)

“Don’t drag feelings out of yourself but think how to perform all the physical actions within the Given Circumstances throughout the play.” (p. 166)

How to work with Physical Actions to create Truth and belief ?

Stanislavski identifies several points that the actor must pay attention to in order to create Truth and Belief through Physical Actions:

- the Physical Actions must create a line

- the Physical Actionss should be worked part by part

- the Physical Actions must be Logical and Sequential

- the Physical Actions must first be practiced first without objects

The Physical Actions must create a line

The actor should create and fix a line made of Physical Actions. This line will act as a path leading the actor in the right direction, that is to Truth, Belief and Experiencing.

“We plotted a line of physical actions and gave life to it. That line is, in its way, a kind of ‘path’. You know it well enough in real life but onstage you have to beat it anew. » (p. 163)

Doing so allows the actor to resist his habit of taking another path, made of clichés and conventions, leading him in the wrong direction of Stock-in-Trade.

“Alongside this, the right line, [the actor] has another, wrong line, ingrained by habit. It is made up of clichés and conventions. He turned off along it momentarily against his will. The wrong line (…) led [him] momentarily away from the right direction and into mere stock-in-trade. To avoid this, [he] has to discover and lay down once again the right line of physical actions. [He] has to ‘tread it down’ further until it has become a ‘path’ which someday will fix the right path for the role once and for all.” (p. 163)

The Physical Actions should be worked part by part

It is often difficult for the actor to create Truth and belief for a whole scene or exercise in one go. The actor should instead divide it into as small and many Physical Actions (Bits) as necessary in order for him to create Truth and Belief.

“Like small, medium-size, big and bigger Bits, actions and so on, in our business there are small, big and bigger truths and moments of belief. If you can’t grasp the truth of a large-scale action at one go, then you will have to divide it into parts and try at least to believe in the smallest of them.”(p. 163)

“You see into what realistic detail, into what small truths we have to go to convince our own nature physically of what we are doing onstage.” (p. 161)

“You can’t get a grip on [a scene] because you want to believe, all in one go (…) ‘In one go’ led you to acting ‘in general’. Try to overcome a difficult exercise in parts, starting with the simplest physical actions, but of course in full accord with the whole. (p. 161)

Achieving one small Truth and moment of Belief this way will then lead the actor to further small Truths, thus building a long succession of small Truths.

“One truth reveals and gives rise to other truths logically, one after the other.” (p. 185)

“I proceeded not by the biggest but by the smallest physical actions, discovering small truths and moments of belief. One gave rise to another, both of them produced a third, a fourth, etc.“ (p. 163)

“If one small truth and moment of belief can put an actor in a creative state then a whole series of such moments, in logical succession, and in sequence, can create a very big truth and a whole, long period of belief. They will support and reinforce each other.” (p. 164)

“If each (…) action is related to the truth, then the whole will flow properly and you will believe it is genuine.” (p. 161)

Discovering a small Truth and moment of Belief can also trigger the discovery of a much bigger Truth.

“Do you know that often by getting the feel of one small truth and one moment of belief in the genuineness of the action, an actor can suddenly see things clearly, can feel himself in the role and believe in the greater truth of the whole play. A moment of living truth suggests the right tone for the entire role.” (p. 163)

“’Small truths evoke bigger truths, bigger and bigger, the very biggest, etc. (…) I am being’ onstage is the result of wanting every bigger truths, even absolute truth itself.” (p. 186)

The Physical Actions must be Logical and Sequential

In order to create Truth and Belief, the Physical Actions must be Logical and Sequential.

“Logic and sequence of the actions (…) helped you achieve the truth.” (p. 167)

Why are the Logic and Sequence of Physical Actions important ?

“Logic and sequence are also part of physical actions. They give them order, stability, meaning and help stimulate action which is genuine, productive and purposeful.” (p. 167)

Logic and Sequence are important:

- for the actor: they will ultimately lead him to Experiencing.

“The orderly logic of physical actions and feelings led you to the truth, the truth evoked belief and together they created [the state of] “I am being’. And what is ‘I am being’ ? That means, I am, I live, I feel, I think as one with the role. In other words ‘I am being’ leads to emotion, to feeling, to experiencing” (p. 186)

- for the audience, who can only Believe in Actions that are Logical and Sequential.

“The audience, as it watches the player’s actions, must also automatically feel the ‘automatic’ process, the logic and sequence of actions with which we are familiar in life. Otherwise they will not believe in what is happening onstage. So give them that logic and sequence in every action.” (p. 171).

How are Logic and Sequence onstage different than in real life ?

In real life, Logic and Sequence happen automatically and Subconsciously, because our Actions have a physical necessity and have become habits thanks to their frequent repetition.

“In real life we don’t think about it. It all happens spontaneously. (…) In life, because the same working actions are frequently repeated you get what I might call an ‘automatic’ logic and sequence of physical and other actions. (…) The subconscious vigilance exercised by our powers of concentration, the instinctive self-monitoring we require appear spontaneously, and invisibly guide us.” (p. 168)

Onstage, our Physical Actions are devoid of both the physical necessity and the force of habit that they have in real life. Therefore, we don’t have any Subconscious self-monitoring for Logic and Sequence of our Actions there.

“Onstage it’s another matter. (…) The biological necessity for physical action disappears onstage, and ‘automatic’ logic and sequence with it, together with the subconscious vigilance and instinctive self-monitoring which are so natural in life.” (p. 168 s.)

Instead, the actor needs to consciously develop a Monitor for Logic and Sequence, until habits are created.

“We have to replace automatic reflexes with a conscious, logical, chronological monitoring of each moment of physical action. In time, thanks to frequent repetition, a habit is created.” (p. 169)

“Initially give [logic and sequence in every action] consciously and then, with time and use, it will become automatic.” (p. 171).

How to work consciously on the logic and sequence of the Physical Actions ?

The actor should work on developing a particular Concentration which focuses on respecting the laws of Nature in each of his Actions.

“The students must continuously train their power of concentration to see to it that the demands nature makes are precisely fulfilled. The students must always feel the logic and sequence of physical action so that it becomes a necessity for them” (p. 172)

Before starting to carry out an Action, the actor should stop and think about it, and make sure he knows the different parts of the Actions and their Logical succession.

“You must first think about, then carry out the action. In this way, thanks to the logic and sequence of what you do, you approach truth by a natural path and from truth you go to belief and thence to genuine experiencing.” (p. 171)

“[The students] must know the constituent parts of major actions and their logical development.” (p. 172)

The conscious Logic and Sequence of an Action doesn’t change whatever the Given Circumstances the Action takes place it. Given Circumstances (made alive with the If) will influence the Action, but this will happen on its own, on a Subconscious level.

“The logic and sequence of all these physical actions doesn’t change whatever the circumstances. (…) The Given Circumstances, the magic or other ‘ifs’ in which the same physical action occurs change. The setting we are in influences the action, but we needn’t worry about that. Nature, our experience of life, habit, the subconscious itself take care of that for us. They do everything we need. What we have to think about is whether the physical action is being carried out properly, logically, and sequentially in the Given Circumstances.” (p. 173)

Actions carried out Logically and Sequentially on stage must be repeated over and over until with time they become habits.

“Do something a hundred times over, understand, recall every single moment and your body, by its nature, will recognize an action you already know and will help you repeat it.” (p. 172)

With time as well, the necessity for Logic and Sequence, which the actor has worked out for his Physical Actions, will extend to other areas of his Acting.

“The need for logic and sequence, for truth and belief carries over, of itself, into all other fields: thoughts, desires, feelings, words.” (p. 169)

“If all aspects of an actor’s nature, as a human being, are working logically, sequentially, with genuine truth and belief, then the process of experiencing is complete.” (p. 169)

Two words of caution

In relation with the self-Monitoring for the Logic and Sequence of Actions, Stanislavski makes two words of caution:

- He warns of the danger of pursuing Logic and Sequence of Physical Actions for their own sake, making Logic and Sequence of Physical Actions an actor’s goal as such. Logic and Sequence are only valuable in so far as they lead the actor to Truth and Belief. But when this means is turned into an end, no Truth and Belief is created, but only lies and conventional (albeit Logical) Actions.

“There is nothing more senseless or dangerous to art than a system for a system’s sake. You must not make it a goal in itself, you must not convert its means into its meaning. That’s the biggest lie of all.” (p. 175)

“You picked holes in every small, physical action not so that you could discover its truth and establish belief in it, but so that you could realize, in a purely external way, the logic and sequence of physical actions as such.” (p. 175)

“Without truth and belief everything that is done onstage, all logical and sequential physical actions, become mere convention, that is they produce lies in which it is impossible to believe.” (p. 175)

- He warns of the danger of letting the (external or internal) Monitoring of the Logic and Sequence of the Actions become an exaggerated critics of what the actor is doing. Excessive critics will have the only effect of paralyzing the actor, putting him away from performing Tasks and leading him to Playacting

“Never allow your art, your creative work, your methods, your psychotechnique and so on turn you into exaggerated, nit-picking critics. That can deprive an actor of his common sense, or induce a state of paralysis.” (p. 175)

“Give it up, otherwise in a very short time an excess of caution, nit-picking and a panicky fear of lies will paralyse you.” (p. 175)

“The actor who is the object of this nit-picking involuntarily stops performing the active task he has selected and starts playacting truth instead. The biggest lie of all is concealed in playacting.” (p. 176)

“To the devil with the nit-picker both outside and inside you – in the audience and even more in you yourselves.” (p. 176)

The actor should instead develop a healthy Monitoring, which limits itself to saying whether what is being done creates Belief or not.

“Develop a healthy, calm, judicious, understanding, true critic in yourself – the actor’s best friend.” (p. 176)

“Those who are monitoring other people’s work should confine themselves to serving as a mirror and to saying honestly, without nit-picking, whether or not you believe what you are seeing and hearing and to indicating those moments which convince you.” (p. 176)

The Physical Actions must be practiced first without objects

Stanislavski advises to first work on Physical Actions without using any real objects, but miming them. If the actor uses real objects, he runs the risk of performing the Actions mindlessly and automatically, following habitual patterns.

But if he needs to mime the objects he is using, the actor, being not used to doing so, will have no choice but to focus his Attention on his Action, to divide it into small Bits and to work on their Logic and Sequence.

“Work with real things (…) proves more difficult than work with ‘nothing’. (…) Because with real things you rush through many actions instinctively, automatically as in daily life, so that as an actor you can’t keep track of them. It is difficult to catch hold of these fleeting actions but, if you botch them, the result is gaps in the logic and sequence of actions which ruin them. In its turn, this botched logic destroys truth, and without truth there is no belief and no experiencing, either for the action or for the audience.” (p. 171)

“With mime (…) willy-nilly, you have to focus your attention on each minute constituent part of a large action. If you don’t do that you cannot recall nor carry out all the subsidiary parts of the whole and, without them, you can’t be aware of the large action as a whole.” (p. 171)

“Miming an object focuses the actor’s concentration first on himself then on physical actions and obliges him to observe them. Miming also helped you to break down large physical actions into their constituent parts and study each of them separately.” (p. 167)

“Do all these physical actions without objects, with ‘nothing’. (…) Miming [forces the actor] to investigate each moment of the physical action (…) Bring this work on concentration to the highest possible degree of technical perfection. (..) After this, place the same physical action in a number of different Given Circumstances and ’ifs’” (p. 173).

Then, after having practiced Physical Actions without objects, the actor can go on working with real objects, but keeping the same Attention and work on Logic and Sequence.

“Even using real things, you have to work on each physical action.” (p. 171)

How to work with psychological actions to create Truth and Belief ?

How should the actor approach an action or moment which has no physical or outer aspects, but is purely psychological ? An action which is made not of movements but of Feelings ? This could be what Stanislavski calls a moment of “tragic inaction”, that is a moment where a character stands stock still, frozen, in a highly complex psychological state, for example after having got some tragic news or made a tragic realization.

For such a moment to be experienced both by the actor and the audience as true and Believable, it should be Logical and Sequential, as Physical Actions.

“You need a clear plan and a line of inner action. To establish that you need to know the nature, logic and sequence of feelings.” (p. 180)

The problem is that the Logic and Sequence of Feelings is much more elusive than the Logic and Sequence of Physical Actions.

“Up till now we’ve been dealing with the logic and sequence of physical actions which are palpable, visible, accessible to us Now we’ve encountered the problem of the logic and sequence of elusive, inaccessible, unstable inner feelings. This area, this new task which confronts you is notoriously complex.” (p. 180)

To deal with this complexity, it’s important to first consider these purely inner moments as being no less active or dynamic than a Physical Action: in a moment of tragic inaction, there is indeed an intense inner activity taking place inside the character, in his Imagination – the character is intensively thinking of what will happen to him, what he will do.

“Before taking a decision people’s imagination is highly active. With their inner eye they see what and how things might happen and mentally go through the actions they plan. Actors physically feel the things they are thinking about (…) Mental images of actions stimulate the most important thing of all – inner dynamism, the impulse to external action. (…) This entire process takes place in the world in which we normally create. An actor’s work is done not in real life, but in an imaginary life that does not, but could, exist. (…) Therefore (…) when we speak of an imaginary life and imaginary actions, we should relate to them as we would to genuine, real, physical acts.” (p. 181).

It’s on these inner Actions – this mental anticipation and planning– and their Logic and Sequence that the actor should focus his Attention on, instead of the elusive Feelings.

“The secret of this technique is that since we cannot cope with the complex problem of the logic of feelings, we leave it aside and turn our enquiries to something which is more accessible to us – the logic of action.” (p. 183).

The actor should do so by asking himself what he would do (in his Imagination) if he were to fall into a situation of “tragic inaction”?

“A method which is absurdly simple (…) consists in asking myself, “What would I do in real life if I fell into ‘tragic inaction’”? Just answer this question in a natural, human way and no more. (…) I turn to simple physical action for help with feeling.” (p. 181)

The actor should “write down all [his] ideas on paper then translate them into Action” (p. 182). Translating them into Actions here means seeing, with his Inner Eye, Mental Images of Actions.

“So, you respond to the question, ‘What would I do if I were in a state of tragic inaction?, i.e., in a highly complex psychological state, no in scientific terms but through a series of highly logical, sequential actions.” (p. 183)

“Every time you repeat a pause of ‘tragic inaction’, the moment you perform it, go over your ideas once again. They will come to you, each day, in a slightly different form.”(p. 183)

“I had to be perfectly still, and ‘tragic inaction’ turned out to be extremely active. Both were necessary for me to concentrate all my energy and strength on the work my imagination and mind were doing.” (p. 185)

The Logical Sequence of these Actions (that is the working of the Imagination, the Mental Images of Physical Actions) will automatically create a Logical Sequence of the Feelings related to these Actions.

“Having created a logical sequence of physical actions, we are aware, if we pay attention, that another line is being created inside us, parallel to it: the logic and sequence of our feelings. (…) They are indissolubly linked to the life of [the actions they give rise to].” (p. 183)

“This is yet another convincing example of how the logic and sequence of physical and psychological actions, when justified, leads to truth and belief of feelings.” (p. 183)

How to deal with lies ?

The opposite of creating Truth is creating lies. How should the actor relate to them ?

What are the wrong ways to deal with lies ?

Stanislavski first points two wrong ways of relating to lies:

- Thinking only about lies out of fear of them

“[There are] two different types of actor [who both] hate lying onstage, but each in their own way. [The first] is panic-stricken by it and so concentrates only on lies. (…) [He] doesn’t give a thought to truth.(…), as his fear of lying has [him] completely in its grip. That is total slavery in which there can be no question of creative work. (…) Need I tell you that the struggle against lying, (…) cannot lead to anything except overacting.” (p. 158)

- Not thinking at all about lies out of love for Truth

“With [the second type of actor] we find the same servitude caused not by fear of lies but, on the contrary, by a passionate love of truth. He gives no thought to the first as he is completely taken up with the second. Need I tell you that (…) the love of truth for truth’s sake, cannot lead to anything except overacting.” (p. 158)

What is the right way to deal with lies ?

To develop a better and healthier relation to lies, here are a few points an actor should have in mind:

- The actor should focus not on fighting lies but on performing Truthful Actions that will create Belief in his fellow actors

“[We can guard against creating lies] by asking two questions (…): ‘Am I doing what I should, or struggling against lies ?’ We go onstage not to struggle against our defects but to perform actions which are genuine, productive and fit for the purpose. If they achieve their goal that means the lie has been conquered.” (p. 158)

“To check whether your actions are truthful or not ask yourself another question: ‘For whom am I doing what I do, for myself or for other audience, or (…) for my fellow actor?’ You know that the actor is not his own judge in performance. Neither is the audience. (…) The judge is your fellow actor. If you have an effect on your fellow actor, if you oblige him to believe in the truth of your own feelings and there is communication, that means you have achieved your creative goal, and lies have been conquered.” (p. 158)

- When an actor notices a lie, that is a moment of Playacting, he should push it away by replacing it with a Truthful Task and Action.

“There is another way to combat lies. (…) Uproot them (…) and plant a seed of truth under the new lie as it appears. (…) Properly justified ‘ifs’, Given Circumstances, compelling tasks, truthful actions will push out clichés, playacting and lies. (…) This process, which we call the eradication of lies and clichés, must occur unnoticed, as a matter of habit, constantly monitoring every step we take onstage.” (p. 159)

- Therefore, a lie can act as a a signpost: it allows the actor to realize he as momentarily ventured on the wrong path and to go back on the right track.

“You can derive benefit from lies too if you approach them intelligently. A lie is a tuning fork for what the actor has no need to do. It’s no great disaster if momentarily we make a mistake, and hit the wrong note. The important thing is to use this as a tuning fork to define the limits of the credible, that is, of truth, so that at the very moment we go wrong it sets us back on the right path. (…) This process of self-monitoring is essential during creative work, and it must be constant.” (p. 159)

- To summarize we could say that the actor should feel neither an exaggerated passion for Truth nor an exaggerated fear of lies, since both only lead to lies. Instead, he should develop a calm and equitable relation to both of Truth and lies, and remember that lies are only important in so far as they can help discover Truth, and Truth is only important in so far as it creates Belief.

“Never exaggerate the striving for truth or the significance of lies. A passion for the first leads to playacting truth for truth’s sake. That is the worst of all lies. As far as extreme fear of lies in concerned that created an unnatural caution which is also one of the biggest theatrical ‘lies’. You must relate to this last, as to truth onstage, calmly, equitably, without nit-picking. Truth is needed in the theatre in so far as it can sincerely be believed.” (p. 159)

“Look for the lies in so far as it helps you discover the truth.” (p. 175)

Previous chapter: §7. Bits and Tasks (Konstantin Stanislavski, An Actor’s Work)

Next chapter: §9. Emotion Memory(Konstantin Stanislavski, An Actor’s Work)

Table of contents: An Actor’s Work (Konstantin Stanislavski)